How the ITALIAN MEDIEVAL GARDEN could contribute to the construction of a restoring dialogue with today’s ecological crisis?

Italy’s history has been strongly marked by the Roman Empire event; it is the event on the top of the list when giving a lecture to this territory, and with all meaning. However, there are other valuable events that have had an indelible legacy on human’s evolution quest, as it is the case of the Italian mediaeval garden: an element whose origin and performance opens a very interesting conversation around landscape whilst also offering us potential & meaningful scenarios to reinforce the contemporary human landscape stance against climate change: A landscape that needs care and attention to be able to adapt to the velocity of this phenomena.

The maximum expression of the Italian garden could be reflected in the Villa D’Este, Tivoli (XVI C. – World Heritage Site-UNESCO) an event that did not appear suddenly in an eye blink but, on the contrary, by crossing an historic path lasting centuries. To come up with this extraordinary artwork it was necessary to walk within a mediaeval alchemy that remembers us how extraordinary and exceptional creations can emerge when having syncretism and when meeting the symbolic and figurative dimensions at the same rate/extent in any human creation.

It could be said that this journey started up due to the fall of the Roman Empire, and later, to the dead of the prophet Muhammad: two events that trigger a shift from the Arabian Peninsula to the Mediterranean Sea and provoke a very interesting syncretism between romans (Christian tradition) and Muslims (Islamic tradition), with special occurrence in the gardens.

The encounter between these two traditions was flourishing and unique, perhaps due to the fact they already shared a common lecture and sense towards the garden, as both saw this place as the medium on terrestrial dimension to communicate with God. On one hand, Christians had the Hortus Conclusus: a sacred place at the heart of the monasteries totally disconnected from secular activity and devoted to meditation and divine harmony.

On the other hand, Muslims had the garden as a place for recalling the paradise, as the Koran states it and as it is also depicted in the Garden of fidelity painting, a place devoted to contemplation and stillness. Additionally, they also share compositional similarities: both were private clusters in a square shape divided in 4 sections by a cross, and both had an important presence of water.

Painting The garden of fidelity in Kabul, the paradise. Image courtesy of Victoria & Albert Museum

There is one detail that needs a special attention, a key point that makes the whole difference and brings us here to have this discussion: it is the way the food plays its role in these gardens, which looks simple, but it isn’t when looking at it in comparison to our today’s gardens: not having at all (or in its majority) the presence of this element.

Although both Christians and Muslims have this element, food, as a relevant-determinant in their gardens, they arrange it differently: in the Monastery Garden the food appearance takes place in other two garden’s typologies and not mixed with the sacred one mentioned before as it is strongly defined by a flower-fill meadow. On one hand, there is the Horti, which is a garden totally dedicated to the vegetables and medicinal plants that monks would bring from their pilgrimages. On the other hand, there is the cemetery, a sacred-funerary garden with an orchard that is not totally private or enclosed as the cluster. In the case of the Islamic garden, the food appearance takes place in the paradise itself, they don’t have it separate, and they give special attention to the use of fruit plants.

Here is where the concept of UTILITARIAN & SYMBOLIC comes along, both cultures had a deep deal with these two spheres in their garden’s creation. Therefore, at the time of mixing and exchanging each one’s gardens values everything just expanded and potential creations started to happen: There was an important trade of plants that later will be important for the culture of italian territory, as it was for example between the XI-XIII centuries, when the Arabs brought to Sicily unknown trees: almond, peach, pomegranates, banana, and later became heritage of the mediterranean.

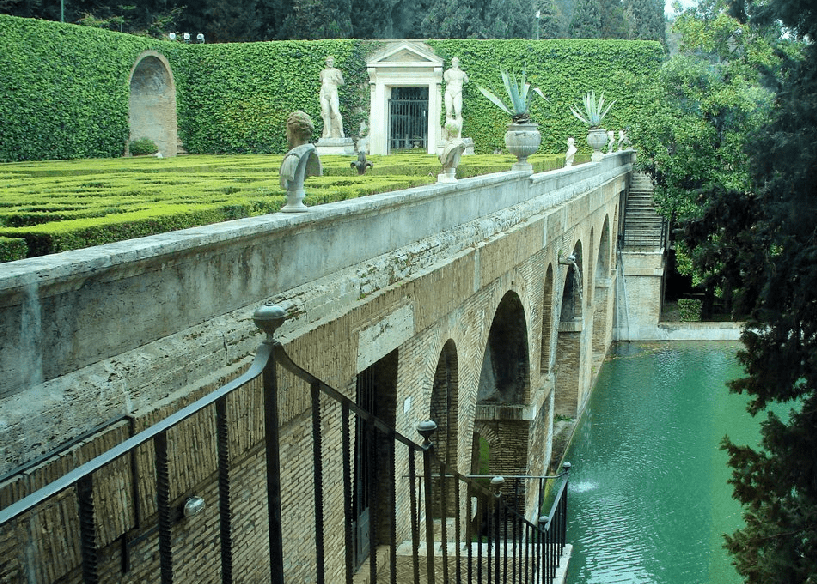

The scale of the garden grew to embrace and empower all essential elements from both traditions, having always the PRODUCTIVE (utilitarian) and AESTHETIC (symbolic) value leading the composition: a garden was then composed by orchards, kitchen gardens (Horti), flowerbeds, medicinal herbs, wooded areas, pools, mazes and fountains and water details with advanced hydraulic engineering. We could see this gradual transformation and syncretism from the Alhambra, in Spain to some villas in Italy, such as Villa Rufolo or Villa Fiesole.

Additionally, during this alchemy, a new garden’s definition emerged: “a garden is for the cultivation of land & cultivation of the soul” given by Leon Alberti Baptiste in its treatise. There was nothing else more accurate to refer to that setting up the garden was experimenting at that moment; the most relevant and powerful impression that we should give eco today. This is a state that has become tangible not just in Villa d’Este but also in most of the Palladian, Tuscan and Roman Villas.

Unfortunately, this marriage between the utilitarian & symbolic started to vanish at some point, from the XVII century on. The french garden took the italian model as a base to its but they enlarged the scale in a way that this relation was unbalanced and the aesthetic value was taking the relevant role. Then the English garden came along and it totally erased the relation between utilitarian-symbolic values, as they enlarged even more the scale of the gardens and wanted to refer to nature as something wild, which put a distance between man & nature, and more strongly, man & food. Eventually, the garden was seen as something strictly aesthetic and exclusive as it didn’t represent any more spiritual-collective traditions but individual explorations, as it was in modern periods.

How can all of this discussion make a difference in the ecological crisis today? Well, we are certain that climate change is something we can not stop but adapt to, and this discussion gives light to three main facts that could be very pertinent to look carefully and learn from while having this global conversation.

The first one, is the syncretism event, a factor that let us see very positive tangible results, and therefore could encourage us to mimic this kind of cultural shift in which there is a tangible exchange of knowledge and interpretations between different territories and ideologies in a way that does not exclude or colonise one to each other, but instead boost an horizontal and clear conversation between all the involved. It would be especially interesting if we could start to have this shift between ancestral, peasants-farmers, and citizens‘ practices and knowledge regarding the matter of the garden, the food, the spirituality and religion dimension.

The second one, is the powerful symbiosis-equilibrium that results from the marriage between the symbolic and utilitarian conceptions when creating a garden. This fact lets us see the noticeable appropriation and nourishment humans can have towards gardens if having both productive & symbolic facts active. This opens a path of exploration inviting us to look for a narrative and methodology able to redefine the symbolic-utilitarian side of contemporary gardens by framing it in an ecological role.

Finally, the third one is the high relevance of scale when recreating a garden. This condition lets us see how determinant can be the size of a garden to make possible the CULTIVATION OF LAND & SOUL. Furthermore, when having a look at this more than twice, we could all naturally coincide in the fact that it should start from the domestic scale to really achieve this cultivation in human daily life. It is just unbearable and depressing to have our food thousands of metres away in the countryside and living on a impermeable floor our whole life; a reality that just collapses the ecological dynamic in any place for all the energy required to bring food to our body, our souls.

This discussion just opened a lot of questions to go and explore and try to find possible answers to the ecological crisis. What should be the symbolic meaning of a contemporary garden? What should be the utilitarian meaning of contemporary garden? How to decrease the garden scale, or even further, how to take it back to our lives? How to make possible the cultivation of land and soul in daily human life? How could gardens play a medium to materialise human’s role in ecological crisis?

REFERENCES

Pizzoni, F. (1999). THE GARDEN A history in Landscape and Art. Great Britain: Aurum Press Ltd.

Additionally, this discussion was inspired also in the course Landscape, Culture & History given by Filippo Pizzoni and Mariacristina Loi at the Politecnico di Milano, Italy.